Mahan Doğrusöz: What would be your analytic take on the origins of the sadomasochistic nature of love in Turkish culture? And why is there still such a strong tendency to take pleasure from pain in Turkish culture?

Yavuz Erten: It is about an aggressive mode of relating in terms of object relations. This mode of relationship is characterized by a victim and a victimizer, a persecutor and a persecuted. I believe that a number of historical traumas lie at the root of this mode of relating. It is present in every interaction from friendships to employee-employer relationships, and child-mother relationships, even in the slightest encounter in the traffic. It somehow emerges constantly in every encounter. One wonders how it is possible for just a momentary encounter in the traffic to be so aggressively charged. This violence is mostly derived from the traumas which were internalized but could not be “metabolized”. So the scene of violence is created over and over again as an “enactment”. I believe that traumas are the foundation of being human, but their severity may escalate, varying from one culture to another. In this context, since Turkish culture is “a highly-charged and burdened culture” and we have scenes that we have not yet reckoned with, we re-enact them over and over again either in the role of a victim, or a persecutor. And, of course, sexuality is no exception, because we know that erotic love involves some sort of “regression”, a regression to the naked areas of the psyche. It is not just the body that is naked, but also the psyche.

Mahan Doğrusöz: It is the moment when an individual returns to his or her most vulnerable state…

Yavuz Erten: Yes, one is most vulnerable at the moment of sexuality… where we get a chance to know the real person… If the individual has not sufficiently “metabolized” this spiral of violence, aggression comes out very strongly in the multi-faceted nakedness of sexuality.

Mahan Doğrusöz: To sum up, one carries the burden of object relations not only of the family, but of the entire society…

Yavuz Erten: Certainly. I regard all of us as members of a big family. The smaller families within the big family certainly reflect some aspects of the bigger family. On the other hand, psychosexual development seeks to follow its own course whose target is to maintain the continuity of the species. The “journey” of psychosexual development from the most basic cellular formation to the highest intellectual level of our romantic affairs is, in my view, comparable to the plants that grow on flat walls. Think about it, the plants that grow on concrete walls… They spring out of a crack on the concrete, climb up to a piece of dirt, change direction, become twisted, shed skin, but keep going. Freud said “the drive never ceases to strive”. The drive “works with” whatever material it has on hand. And just like the plant climbing on concrete wall, if it finds itself in such a “violent” scenario, that is, if the world consists of the oppressors and the oppressed, then it naturally follows that sexuality consists of the fuckers and the fucked. So it is no longer an experience of “making love”, but turns to an experience of “domination” in which one takes pleasure from dominating, and the other kind of takes pleasure from being dominated.

Mahan Doğrusöz: Going back to the beginning of our interview, you mentioned the historical traumas that we have not yet confronted and metabolized. What are those traumas?

Yavuz Erten: I believe that we have a very bloody history. Yet I know that we are not alone in this sense, considering the whole of humanity. But some cultures have confronted with, mentalized and metabolized these issues to a greater degree. The Western societies often tend to strive for this. For instance, the killing of Algerian people by France was a big massacre, for which the state of France has not apologized yet, but the French society produced numerous books, articles, documentaries, group studies, and movies about it.

Mahan Doğrusöz: Does it also correspond to a “healing process”?

Yavuz Erten: Yes, it is indeed a healing process, because when such issues are not worked through, they remain “raw” and encapsulate a part of the psyche. The individual keeps repeating this scene either as a victim, as a persecutor, or as a witness.

Mahan Doğrusöz: So the individual is identified with one aspect of the trauma.

Yavuz Erten: Yes, it may be the executioner, or the victim, and also the witness or sometimes the rescuer. This is what the “third corner” is all about. In our history, there are so many traumatic incidents that took place in Anatolia. There is the Armenian issue, for example, and what we did to the minorities. But there are also things that were done to us. We do not talk about these, either. For instance, my ancestors are originally from the Balkans. During the Ottoman withdrawal from the Balkans, around 5 million people were lost, either missing or dead. Children were lost and people were killed during that migration process which lasted from the 1900’s until the early 1920’s. Somehow we do not work through what was done to us, either. Here is an intriguing question: We may assume that we cannot work through our acts of cruelty due to the feelings of guilt. Why, then, cannot we work through what was done against us? Is it because there is an intimate connection between what was done to us and what we did to others? It raises a question mark in my mind.

Mahan Doğrusöz: You mentioned that the tradition of confrontation is stronger in the West. In this sense, it is no coincidence that psychoanalysis was born in the West, and failed to be integrated into the mainstream Turkish culture.

Yavuz Erten: I agree wholeheartedly. Our dominant discourse is “don’t get me started”. Years ago, I saw Alev Alatlı talking about the Armenian issue in a TV show, and she said: “Don’t get me started. It is what it is. We do not want to talk about this, nor –I have suffered many losses in the Balkans– nor do I want to talk about it.” I think it is interesting to hear this from a Turkish intellectual while we hear the opposite from a Western intellectual. Our intellectuals prefer “let’s not talk about it” for some reason.

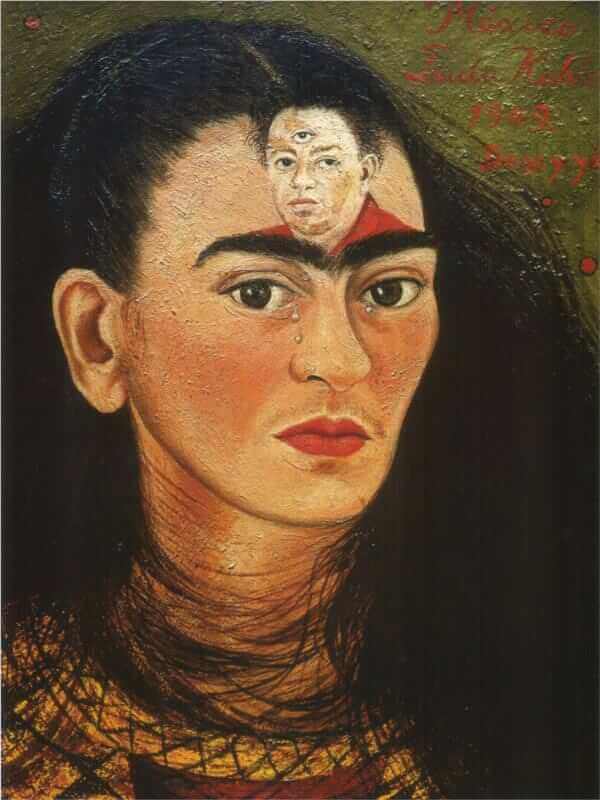

Diego and I, Frida Kahlo, 1949

Mahan Doğrusöz: I would like to return to the theme of sadomasochistic love that we touched upon earlier. It is often described as men representing its sadistic aspect, and women representing the masochistic aspect. Sylvia Plath has a famous line, “Every woman adores a fascist,” she says. When I look around, I see that this “line” actually holds true for the women in Turkey. Women adore men in relationships where they are victimized, and define this sadomasochistic relationship as love. In this context, how should we describe the interaction between gender and sadomasochistic love?

Yavuz Erten: As a psychoanalyst, I am a little confused about “gender”, or more precisely about the Turkish translation of “gender”. I am trying to understand gender from a psychoanalytic perspective. The Turkish translation of gender [highlighting only the “social” aspect of gender identity] is not really compatible with the psychoanalytic perspective. Still I believe it is an important concept in terms of social sciences or social policies. The psychoanalytic perspective needs a more “in-between” concept. That’s why it is not sufficient for us to highlight the social aspect only. Here is another way to think about it: There is “sex” referring to the biological attributes, and there is sexuality. Sexuality is a masquerade ball, involving scripts, roles, games, and fantasies. Sexuality is a psychological arena that is based on mental representations. What we need in psychoanalysis is a term that would describe the conversion of sex in the biological sense into the sex of this representational realm to be used in sexuality. For example, Hakan Kızıltan, an esteemed colleague of mine, recently suggested an alternative translation: “sex of the psyche”. It captures the essence of my thoughts.

We may conceive of instinct as the bare electric charge while drive is its conversion into a computer program. This is the path from instinct to drive, and similarly from “sex” to “gender”. It is not possible to differentiate gender into simply man and woman. Our gender is a cocktail in this sense.

Mahan Doğrusöz: Are you referring to Freud’s concept of bisexuality?

Yavuz Erten: I am referring to both bisexuality and cross-sexuality. I believe that everyone has different compositions of heterosexual and homosexual and bisexual tendencies, but when it comes to homosexuality, it is unique to everyone depending on the attributes of each person’s script. Just like all fingerprints are similar, but never the same…

Mahan Doğrusöz: You mean that there are no two distinct categories as man and woman.

Yavuz Erten: Yes, that is what I mean… Yet the concept of gender, when considered only in its social aspect, exogenizes the matter far too much according to the psychoanalytic point of view. I believe that “gender” is specific to each individual. It is a unique equation, a unique formula based on each individual’s own representations.

Mahan Doğrusöz: So you probably consider this question to be overgeneralizing.

Yavuz Erten: I expressed a concern of mine about the word of “gender”, but I am aware that stereotypes exist on a social level. These social roles are one of the ingredients of the cocktail I mentioned earlier. It certainly colors the cocktail, but does not explain everything by itself. Gender is something that is “constructed”. One is not born as a man or a woman in this sense. The society strives quite a lot to construct this. The government, the educational system, family, traditions, fashion, consumption-production relationships, they all create it somehow, also involving certain theoretical constructions. For example, Freud described female sexuality as passive and the male sexuality as active. He conceptualized female sexuality as more receptive, something to be penetrated, encroached upon, conquered. This view is still effective in the mainstream psychoanalysis. There are those analysts who adopt a somewhat different approach depending on social trends, but this view is still prevalent. Otto Kernberg’s Love Relations is perhaps one of the best books to express the mainstream psychoanalytic thinking. We see that this way of thinking still goes on in some way. It should be a topic of debate. Do we actually possess such biological passivity and activity? Or is it possible for men and women to exhibit more androgynous features and experience a more fluid dance of activity and passivity? It is an important aspect of the debates around gender. Is gender fixed or fluid? Feminist psychoanalysts, progressive psychoanalysts, and so on usually support the views leaning towards “fluidity”.

Mahan Doğrusöz: What is your stance in these debates?

Yavuz Erten: I encounter this sort of passive-active polarity between men and women in the population that I see. But this population is the product of this age, this context, and these constructions.

Mahan Doğrusöz: You are saying that it is not possible to interpret this because we cannot analyze an essence that is isolated from this context.

Yavuz Erten: That is right, but I do encounter such themes as you mentioned in the population that I see. For example, the woman is in love with a persecutor, as you said earlier. She complains about him in tears, but she cannot break free from the relationship with him. She can achieve an orgasm when the masochistic aspect is dominant in sexuality, and pays all the price for it. In the course of working through her traumas, not only about sexuality, but the whole object relations that make her who she is, as they are enacted in the room and as she gains insight into them, the degree of violence in the relationship decreases. As these themes are worked through, the whole experience becomes like an enjoyable dance involving both passivity and activity with the roles changing from time to time. Some people experience this change as losing the passion and excitement, and becoming dull, but then different pleasures begin to emerge gradually.

Mahan Doğrusöz: So they begin to explore a new arena, to take pleasure from pleasure rather than from pain?

Yavuz Erten: Yes, it becomes making love, an experience that is enjoyed together, no longer merely the pleasure derived necessarily from the re-enactment of a certain scene of “violence”. The individual explores “making love” rather than “fucking-getting fucked”. But I do not believe that sexuality can possibly exist without some measure of aggression.

Mahan Doğrusöz: It would not be sexuality then…

Yavuz Erten: Right. Aggression also has a role in the sexual construct. But it may be experienced in a transitional space. It is another story when the transitional space collapses, when it is no longer play, but one actually beats up the other. The dominant view in the mainstream psychoanalysis used to be that women have masochistic tendencies and men have sadistic tendencies which are exaggerated in the case of psychopathology. And in non-pathological cases, they do not swing centrifugally, but remain in the middle with a little bit of both, and even become part of the game. But in pathological cases, masochistic perversions and sadistic perversions begin to appear. Like you said earlier, aggression puts sexuality in parentheses. Then it is no longer a situation of sexuality involving aggression, but of aggression involving sexuality.

Mahan Doğrusöz: Another question I have is about the patriarchal Turkish family structure. Interestingly enough, mother is a very dominant figure in the family notwithstanding its patriarchal nature. It seems quite “ironic” to me a culture with such female dominance can be so misogynistic. Turkish culture contains an intense rage against the female. We see its reflections in the animosity between the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, or in women’s envy of other women. So women are also the carriers of this misogynistic culture.

Yavuz Erten: I can speculate on the social phenomena, but we first need to reflect on what is going on with regard to the internal world and to the family dynamics which form the primary object relationships. Men are usually about the outside. In the mammals, too, male is more on the outside, while the mother is often besides the infant. In that sense, the mother and the infant are in a highly symbiotic state. The father, as the “other” in this relationship, offers a third dimension and a way out of this “symbiotic strangulation”. This emancipatory function of the father is crucial. It may not be the actual father necessarily, but a woman apart from the mother in the family who performs the paternal function. Kristeva represents it in her concept of the “abject”, referring to the “devouring” nature of the mother. Motherhood has an eerie and suffocating aspect to it in that sense. And from the point of the mother, post-partum depression is no coincidence. There are “hellish” aspects of that highly romanticized relationship between the mother and the infant. Mother is also a “cavity” that the infant needs to get out of. Again referring to Kristeva, that “abject” is a corpse which is eventually buried. Mother throws out the child as an “abject”, yet she is also like an “abject” herself which the child needs to remove from his being. It is not the death of the mother that we are talking about here, but the symbolic death of this mode of relationship with the mother. In the absence of the father, or of the paternal function, both the mother and the child are stuck in this “abject” state. Remember Bertolucci’s movie “La Luna”.

Mahan Doğrusöz: So, in a symbolic sense, the father cannot pull the infant out, and the infant stays in uterus forever “rotting away”.

Yavuz Erten: Lacan compares this to being in the jaws of a crocodile, a metaphor which also represents oral aggression. He describes the paternal function as a “rolling pin” placed at the back of her jaws. The child can escape from the mouth if it is not shut. In some cases, the man who “occupies” the paternal function runs away. Why does he run away? In a way, he saves himself by pawning the child or the children. Because the dynamics of his relationship with his wife are similar to those with his mother, instead of saving the children, he ends up being saved by them.

Mahan Doğrusöz: In this context, men find the courage to separate from their mothers only after they get married and have children.

Yavuz Erten: The infant who is not saved by the father from the jaws of the mother constantly struggles with the maternal image. The witches in children’s tales are very significant in this sense. On the one hand, there is the innocent mother who was killed, like in the story of the Snow White, and on the other hand, there is the step-mother/the witch. The witch is also the mother. The split-off aspects of the mother as good and bad: the Angel Mother and the Witch who Eats Children.

Mahan Doğrusöz: Another face of the mother..

Yavuz Erten: Yes, another face of the mother… Like in Cronenberg’s movie Spider, in which the father kills the mother in liaison with a prostitute and then lives together with her. The child witnesses the murder, but no one believes him when he claims that she is not his mother, that his mother was killed. This is actually a case of psychosis. He begins to create a web-like formation so that the house will blow up when she turns on the gas. The movie depicts beautifully how psychosis takes hold of a person like a spider’s web. Indeed the woman is blown up, and when she is being taken away in the last scene, the father scolds him “What have you done? You killed your mother.” So the woman that appears to be the “other woman” is actually the mother. The child has seen his mother as a “witch” or a “prostitute”. Without the representability of femininity by men and women who have distanced themselves from this archaic mother and who have managed to create “thirdness”, we can never fully mature in our sex and sexuality.

Mahan Doğrusöz: How would you explain the intense envy of women towards other women in this picture? Is it because the mother never wants her daughter to be separated from her to leave her womb that if she is separated and differentiated, she feels rage towards her daughter due to the ensuing competition?

Yavuz Erten: It may be the case in the mother-daughter relationship, but the mother-son relationship is about something else. The son functions as the mother’s penis. He makes up for what she lacks; he completes her, integrates her, and makes her whole by becoming her penis. And when he attempts to go his way to another woman, she asks “where do you think you are going?” You know, at earlier times, mothers would check out brides for their sons in Turkish baths, symbolically choosing the girl they would fancy for their own penis. When the son leaves the mother for another woman, i.e. his bride, the mother flies into a narcissistic rage that says “You are destroying my integrity and taking away a part of me.”

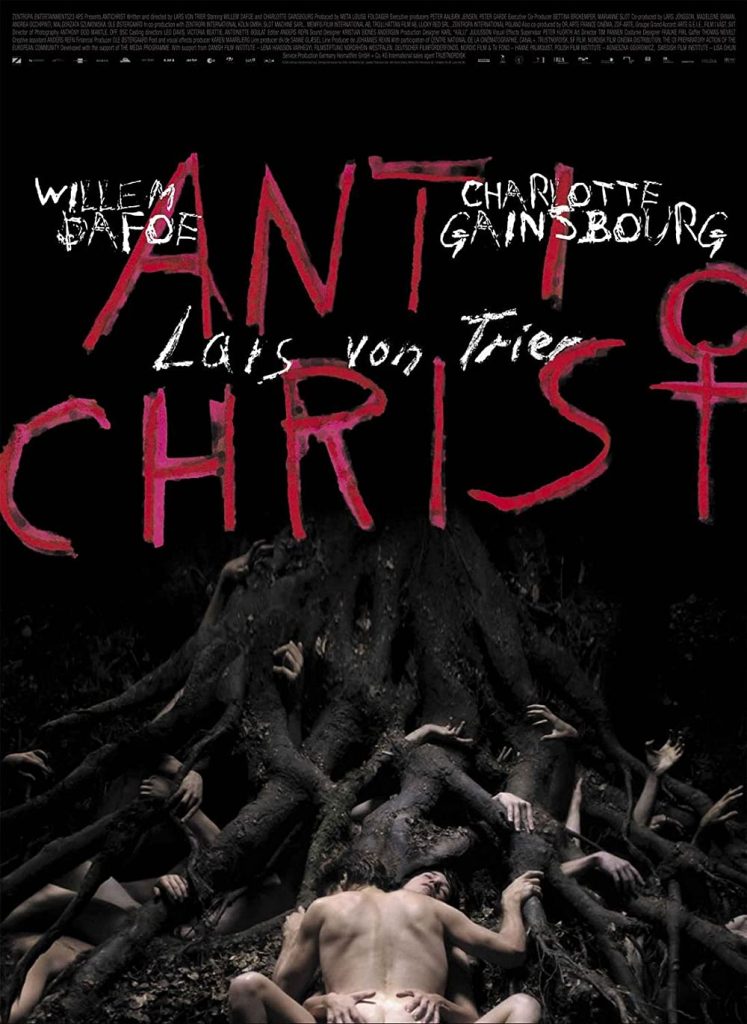

ANTICHRIST

Yet even before the boy-girl differentiation, it is still an issue that is relevant for the child. Gender differentiation occurs at a somewhat later phase. There is something more archaic than that in the mother-infant relationship. Neither the mother nor the child can easily get out of that “cavity”. It is a matter of the nature’s eeriness. Here I am reminded of Lars Von Trier’s movie Antichrist. It refers to the entirely horrific aspect of this archaic motherhood. Lars Von Trier locates this dark cavity into the nature, i.e. within a forest, namely Eden. In the forest, the mother realizes that she has –probably– killed her child, or insinuates that to the audience. At the beginning of the movie, when the mother is having sex with her husband, her infant son is seen to be climbing to the window ledge and trying to catch the snow. The child falls off the window and dies. Then she has a psychotic episode. As the movie goes on in the forest where the couple has gone for her rehabilitation, we gradually find out that she had seen the child out of the corner of her eye, but did not stop. The more she remembers, the more she is drawn to a psychotic vacuum. In the end, the husband kills her. The movie leaves us questioning whether the man knew the whole story from the beginning and did not actually take her there for rehabilitation, but the journey was in fact an execution.

Mahan Doğrusöz: So he was actually intending to kill her.

Yavuz Erten: Yes. If we consider the archaic motherhood that can devour, that has devoured the child, the father intended to kill the mother. In the end, he makes a big fire, puts the mother in the middle of it, and burns her. The big fire, the wood pile, the tongues of flame rising to the sky, they are all reminiscent of the witch-burnings in the Middle Ages.

Mahan Doğrusöz: I hear that the archaic mother is a very powerful being with both goodness and badness, almost possessing a divine power…

Yavuz Erten: Yes, and she offers a very high degree of gratification…

Mahan Doğrusöz: Yet her punishing power is also very strong. I am trying to draw sociological inferences from what you say. You are actually describing an “omnipotent” mother. She seems to be omnipotent in her own mind as well as in the phantasy of the child. But when I look at women within Turkish culture, I see that they are not that powerful in the public sphere. Turkey is ranked the 124th among 135 countries in the WEF Global Gender Gap Index. In other words, women barely “exist” in the public sphere according to the economic, political, and educational indicators. Women are described as omnipotent from a psychoanalytic point of view while they are reduced to nothing in the public arena. What do you think about this?

Yavuz Erten: I think there is a question mark over this issue. As a psychoanalyst, I wonder if the appearance is the whole truth, or is there something else somewhat invisible behind the appearance? Are women actually that powerless? Or, sometimes, you know, how the seemingly weakest is the most powerful. Family system theories also describe how a disturbed member of the family may be the weakest, but also the most influential “determining” factor in the family.

Mahan Doğrusöz: You mean the power of the victim.

Yavuz Erten: We cannot put all victims in the same pot. Especially in these frantic days when our country is in desperate need of social policies to protect women from being murdered… But in the special cases in question here, the victim “manipulates” and governs everything, and all circumstances are arranged according to their needs. If power is defined by the determining influence, we need to stop and think for a minute here. When we look at the family, women have the determining influence, which is probably true for many families. While it may be true within the family, there is a striking minority of women in the parliament, or in other social organizations. So I wonder if there is an internal battle going on at a social level. While women are so influential in the family, in the relationships with children, or in the spousal relations, are men fighting fiercely not to lose power at other strongholds?

Mahan Doğrusöz: How would you explain women’s “rage” against other women, considering everything we have talked so far?

Yavuz Erten: I see women being aggressive to other women in the traffic. They can easily treat others in a way that they would not like to be treated. Here we return to the spiral of violence that we talked about earlier. At that level, there are only two possibilities in the world: insulting or being insulted, shouting or being shouted, fucking or being fucked. When the world is all about these polarities, women may also prefer insulting, shouting and fucking instead of being on the other side. Traffic is a metaphor, of course. People get stuck in these polarities everywhere from the workplace to the university and friendships. Let’s remember the French analyst Jacqueline Schaeffer’s theoretical approach: She mentions “phallic-castrated” pairing as a fixation point in psychosexual development whereby you either become phallic or castrated. She distinguishes phallic from genital. “Genitality” is an advanced phase of maturation both for men and women. It is a phase when such concepts of “activity” and “passivity” begin to lose significance, leaving their place to a different, more “fluid” dance. But at the pairing of “phallic-castrated”, both men and women idealize the phallus. And phallic stage is actually a narcissistic stage. There is a concept called phallic narcissism. It is not related to the penis. For example, if a woman is fixated in the phallic stage, her body may turn into phallus, i.e. her body may become very seductive and powerfully influential. “If the man has a phallus biologically (i.e. penis), I have my entire body (as a phallus),” she says, and adds, “With my body that has become a phallus (and with the seduction it creates), I will strike against his virility which he believes to be his strength and privilege, but is actually his weakness.” A woman who is fixated in the phallic stage may appear very sexy, but there is a saying that “they sexualize everything but genitalize nothing”, that is, she may not have any genital pleasure. She uses her body as a weapon in that struggle.

Mahan Doğrusöz: I also wonder why Turkish men’s narcissism is so fragile and why they cannot develop enough self-confidence to not take everything personally.

Yavuz Erten: I do not believe that it only applies to men. The same can be said for women, too, at least if they have not reached “genitality” properly. It is a matter of being fixated in phallic narcissism. They used to sell long-shaped balloons on the streets. It is almost like how men are walking around. In the end, it is just a balloon. You know, if someone walks around all day with a balloon, everything appears like a needle that might puncture their balloon…

Mahan Doğrusöz: I suppose the fragile masculinity of Turkish men is rooted in the fact how they learn about masculinity via the “mother”. The “balloon” you mentioned is not filled with “genuine” content in that sense.

Yavuz Erten: And it carries a strong femininity in it, which is why it is so homophobic.

Mahan Doğrusöz: I had read a similar interpretation of the “machismo” culture in Latin America, linking the excessively exaggerated and inflated masculinity, i.e. machismo, to the absence of father in the family and to the boy’s attempt to get free from an over-identification with the mother through identification with an artificial and thus exaggerated masculinity.

Yavuz Erten: I think this view is highly applicable to the Turkish culture, as well.

“Dora Maar”, Man Ray, 1936

Mahan Doğrusöz: There has been %1400 increase in femicide over the past 10 years in Turkey. Most of these women are killed by their current or former partners. I interpret this increase due to the narcissistic rage created by the “narcissistic fragility” in men. How do you understand this escalating narcissistic rage?

Yavuz Erten: I believe that former patterns and defenses are collapsing. Along with the collapse of the defensively-organized narcissism, a narcissistic rage arises, accompanied by an intense fear of disintegration. Defenses are actually the lies that an individual or an organism (such as a society) tells itself. They believe those lies more than anyone else. Defenses exist on a social level, too, in the form of social lies. We may conceive of that social body as a self, which can no longer maintain the former excuses and lies, resulting in a narcissistic rage and an intense disintegration anxiety. Regarding the social relationships in terms of state vs. citizen, there used to be an authority with unquestionable power to whom others owed obedience and whose word was the law.

Mahan Doğrusöz: I understand that you transfer this to the relationship between men and women. The authority of men is questioned by women, and it arouses rage in men.

Yavuz Erten: Yes, that’s how I see it. It is like the man says to the woman: “I am dying, and I will kill you, too.” It means “My authority is threatened, and I will make you pay for it.” We cannot say that there is no internal battle in this country while thousands of women are being murdered. “Internal” here refers to the “intrapsychic” as well as “domestic”. I refer to the internal struggle between the feminine and the masculine. For any individual to reach genital maturity, both men and women need to integrate the feminine and the masculine within themselves.

Mahan Doğrusöz: I would like to end with a futuristic question. I believe that we live in a “dystopic” era, in an era of dystopias rather than “utopias”. Therefore, the question involves my “cynicism”, but I wonder about your perspective. As a psychoanalytic thinker, how do you see the future of relationships between men and women in Turkey?

Yavuz Erten: I suppose the biggest change in Turkey should take place in the man and the authority. Our social transformation is dependent on a sort of masculinity and of man who has overcome his homophobia, given up walking around with that “big, long balloon” of phallic narcissism, and come to terms with his deficits and disabilities in life, as well as on a flourishing femininity that has been stunted due to masculinization. Unless these changes occur, the paternal function cannot operate in the society. This is the path to transformation, and if these changes will not happen, neither will social transformation. In the relationship between the state and the individual, there must be changes in the nature of the tyrant state, its police force, soldiers, their weapons, and the oppression exercised either directly or through rationalizations. There will be no transformation as long as they remain the same. And I would like to emphasize again that women also have to change in order to provide a basis for all these.

Change is always difficult. In the course of change, both parties have “vulnerable” and “fragile” aspects. And both parties need to go through a test of maturity. I do not consider it as the relationship between men and women, but as an internal conflict that is expressed in that relationship. Returning to your first question, as we work through the traumas, the traumas will be enacted and do anything to become indispensable. People come to therapy or analysis to become free of certain patterns, but respond to the therapist or the analyst with the pattern from which they want to become free. Let me give you an example of the metaphor that was said to me in my own analysis. The analyst says “your experience is that of an inkfish”, and the patient responds by squirting ink, “Come on, there is no such thing!” The individual does not have self-awareness during enactments. As they are worked through therapeutically in the analytic process, the patient feels like a victim in some way or another as new forms of victimization emerge because the pathological defenses “resist” and the former modes of relating strive to perpetuate themselves.

I do believe that it will be a strain for the man and the authority. It will be a test of maturity for the authority. For example, it will learn in time not to perceive criticism as an insult.

Mahan Doğrusöz: So the man will be reconciled with the woman and also with his feminine side.

Yavuz Erten: Indeed. One of the greatest challenges in therapy and analysis is to work with the “masculine resistances” in men and women. Psychoanalysts know that the resistance of masculinity (or, of the authority) is not easily resolved. It cannot shift to a passive or receptive position, regarding it as highly feminine. It means that interpretations cannot easily get to them. Yet this position is bound to collapse eventually, or, if not, it will have to sustain itself through violence. In this context, it is important to say that “no progress or development is possible without involvement of the human psyche”. Therefore, democracy is crucial. “Internal conflicts” are crucial. It is crucial to be freed from and transform transgenerational traumas. We have to achieve these in order to mature and escape from the phallic narcissism where we are fixated. As individuals and the society, we are so trapped into a corner… Should we be optimistic, thinking like the old saying “it is always darkest before the dawn”? We might also try to catch sight of what the authority shall do next as a mental and social actor…

Yavuz Erten is a psychoanalyst and a clinical psychologist. He is a member of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) and Psike İstanbul. He is the founder of İçgörü Psychotherapy Center. He is a part-time faculty member at İstanbul Bilgi University. He is a founding member, former vice-president, and former secretary-general of Psike İstanbul (İstanbul Psychoanalytical Association for Training, Research, and Development). He is the trainer of the training group formed at IPA Turkey Psychoanalytical Working Group Psike İstanbul. He is also a member of the International Council of Self Psychology. He is the author of Karanlık Odadaki Suretler [Appearances in the Dark Room] (2010) and the co-author of Psikanalizden Dinamik Psikoterapilere [From Psychoanalysis to Dynamic Psychotherapies] (1999) with Cahit Ardalı. He is an editor of the books Psikanalizin Öteki Yüzü: Heinz Kohut [The Other Side of Psychoanalysis: Heinz Kohut] (2003) and Bilim ve Felsefe Açısından Ruhsallık Bilgileri [Knowledge of the Psyche in Science and Philosophy] (2006). He is in the editorial board of the journal Suret [Appearance]. He has a large number of articles published in various journals.

November 2013 © Mahan Doğrusöz

I would like to thank Tuğçe Tokuş for her assistance in the transcription of the interview and to Menekse Arik for the English translation.